From Chapter 7: The Music Trail

Welsh’s earlier musical roots are in punk. The punk of the 1970s and going into the 1980s was an attitude, of which music was its most prominent expression. The attitude was rejection and defiance of the status quo. If it can be attached to a single ‘provocation’, which was also its high water mark, it was the Queen’s Silver Jubilee celebrations on 7 June 1977, ostensibly a public display of warmth, affection and loyalty to the pinnacle of nationhood, wealth and privilege, while the punks saw decay, corruption, and, well, things were just b-o-r-i-n-g.

The chief elements of punk were a do-it-yourself approach, brevity, insolence, and, pinning them all together, egalitarianism. In a major cultural break, punk was an expression of those who were using the newly available drugs – out went alcohol and hash, in came the harder drugs of heroin and cocaine. Punks cross-dressed, some had dangling chains, men wore make-up, hair was grown long and was ferociously gelled into often brightly coloured spikes. Musically, punk pulled away from the rock bands on their faraway concert stages, and their five-minute virtuoso guitar riffs. Way back in ancient history now were the lovable Liverpudlian mop-tops, The Beatles. Naturally, the big bands depended on publicity and they went on tours – they were commercial and professional – but everything purported to be as rough and ready as possible, up close and personal. Punk was smelly, sweaty, noisy, rude and in-yer-face or it wasn’t punk. With so many internal paradoxes, anarchy and contradictions, perhaps punk was not so much a movement as a moment that couldn’t last long. But during this moment, it certainly made some waves: in a sign that the Establishment was badly rattled, there are strong suggestions that the British pop charts were rigged to prevent the Sex Pistols’ track God Save the Queen (and her fascist regime) becoming #1 record in the week of the Jubilee.

By the time Welsh went to London in 1978 to pursue his interest in punk as one biographer almost certainly overstated it, punk was moving into its second phase. With the departure to USA in 1978 and death the following year of Sid Vicious of The Sex Pistols, the shock element had somewhat dissipated. The Clash, if you can pierce through their ranting, addressed serious issues of the day, particularly in their most successful album London Calling, released in UK 1979. Rising sea levels (the Thames Barrier was built a few years later), police violence (well documented), and a ‘nuclear era’ – or was it ‘error’? – (an ever-present anxiety in the Cold War) are the concerns of the title track. It certainly looks like Welsh has borrowed and adapted The Clash’s title to give him the episode title ‘London Crawling’, although the content of the episode is more of a complaint than a rant. Renton turns up in London, but the place has few charms. It crawls.

More appositely, however, we could say the book as a whole is a rant on serious issues: violence, heroin addiction, HIV/AIDS, and a youthful lust for life. Welsh turned to writing. Literature, theatre and cinema generally lag behind music and artwork (think of graffiti), which are more immediate expressions of a cultural moment or movement. In parts, Trainspotting can be viewed as performance literature, something close to stand-up. Or think of the book as a series of punk songs. Let’s try one episode. Supply your own music – it doesn’t need to be sophisticated – in your head. To go on location we can stand on the grass opposite Welsh’s flat at No. 2 Wellington Place.

DEID DUGS

Pit bull, shit bull, bullshit dug,

Friend ay the dealer, nae friend ay mine.

Peaceful day in the park

But there’s nae peace till this bastard’s deid

By my hand.

Shell suit, shell suit, stand aside

Ugly brute in my sights.

Oh ya dancer! I got him full square

OAN HIS AIRSE!

Shean shaysh tae me ye’re a beautiful shot.

That’sh you an me Shean, we’re beautiful men

Cos I am the Sick Boy the scourge of the schemie

An blooterer ay the brain-deid.

Dug attached tae his maister’s airm

This is real, this is me.

Baseball bat inside the collar,

A twist and a shout an the bastard’s deid!

Polisman says Ah’m a hero ay sorts.

Only doing my duty, sarge, have a nice day

Cos Marianne’s goannae git some stick the night!

You could try at home giving the single-incident episodes similar treatment: ‘Her Man’; ‘Speedy Recruitment’; ‘A Disappointment’; ‘Feeling Free’; ‘The Elusive Mr Hunt’; ‘Easy Money for the Professionals’; ‘A Present’; ‘Eating Out’; and, perhaps the most fertile of all, ‘A Scottish Soldier’. A dark, dark number could be made out of the ‘Junk Dilemmas’, with perhaps a reprise from ‘Straight Dilemmas No. 1’.

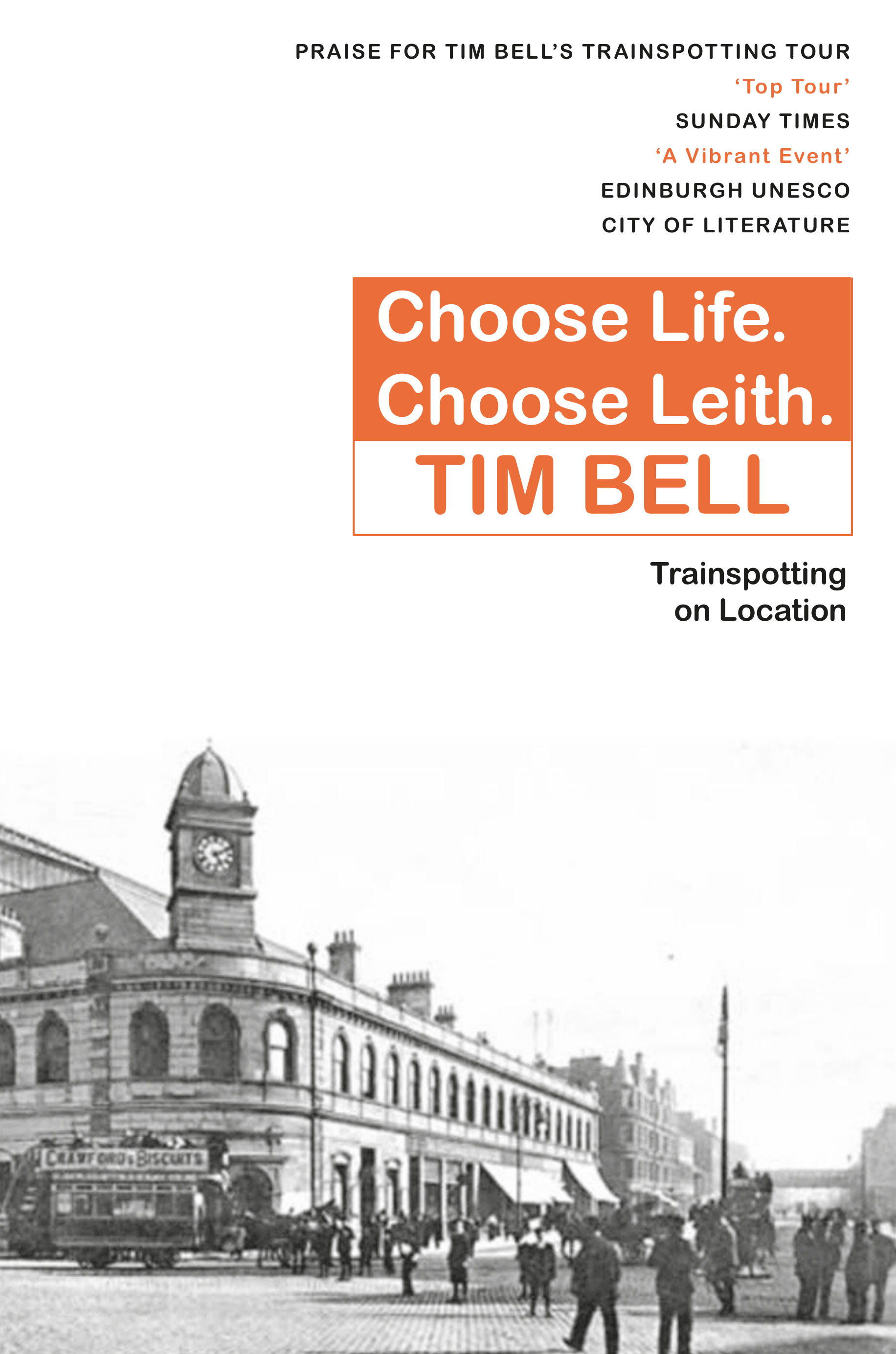

Punk’s most iconic and enduring image is of the Queen in the run up to her Silver Jubilee as monarch in 1977, smiling, with a safety pin through her lip, punk-style. Disrespectful or what? In ‘Na Na and Other Nazis’ Spud mooches about on a hot day. He gravitates towards the Foot of the Walk, where stands the best known statue in Leith, modest in size but unveiled with great ceremony almost a century previously in memory and honour of Queen Victoria, Empress of India. It is also, following the Boer War, a monument to the elevated virtues of patriotism and loyalty with, in a bas-relief on the plinth, particular reference to the Leith Volunteers (the 7th (Leith) Battalion, The Royal Scots). It was deliberately placed in the heart of the town. Spud clocks her presence as ‘Queen Sticky-Vicky’ (p.120), which at first sight is simply a bit of youthful cheek. Is this Welsh’s riposte to Victoria’s remark in 1842 that Leith ‘is not a pretty town’? Probably not. The several references in the book to Benidorm (Spain), a popular place for cheap sunshine in the 1980s, make something different out of ‘Queen Sticky-Vicky’. There was a famous nude stage act in a Benidorm night club in which Queen Sticky-Vicky produced an astonishing range of objects from her vagina: silk handkerchiefs, ping-pong balls, beer bottles, and the rest. Welsh’s ‘Queen Sticky-Vicky’ is a literary version of the safety pin. Let’s say Spud’s throwaway line is Trainspotting’s most punk moment.